Curious Paths of Thought

It is the physical qualities of an image that not only help define the technique of the artwork, but also play on our overall perception of it. To call these works “drawings” may well be read as a contradiction in terms, when one considers that they have been made by a machine. Drawing, by definition and tradition, contains the idea of a gesture; a movement that utilises tools, marking the medium through bodily expression. To draw using a machine – or rather, to have the machine draw – raises eyebrows. It challenges our views on what drawing is, and makes us reevaluate the role of technology in artistic expression – a partnership that has in fact existed since the dawn of mechanisation. Doing this today and with the aid of the computer opens the discipline up to an exciting range of possibilities that have only just begun.

Back in the 1960s, computers had no user interface. The only way to get something done on a computer was to either load a programme onto its memory, or write one yourself. Furthermore, there was no immediate means to visualise your programme’s output. For that, one had to print it – and more often than not, this was done using a plotter. It was at this point that a few fortunate engineers foresaw an artistic use for it and started feeding the machine with programmes that would output visuals.

The heydays of the pen plotter in the 70s and 80s were followed by their total obsolescence with the advent of faster printing technologies. However, in the early 2000s, on the wave of DIY CNCs and 3D printing machines, many people’s curiosity and fascination brought them back – including in one project I worked on. In 2014 I collaborated with one of my students to create a drawing machine. We named the machine SAM and a few years later it was invited to be featured in a workshop and installation organised by Julien in Bordeaux. It was here that I had the opportunity to experience the beginnings of Julien’s own interest in plotters. Little did I realise at the time that his curiosity would become the stirrings necessary for him to embark upon a long and successful artistic journey devoted to drawing with the machine.

If the machine is to draw, what does it draw? This is a perfectly pertinent question for which there are many answers. For Julien, the answers have come quite simply in the doing – through the act of sitting down and working with both the computer and plotter. The programmed computer is capable of generating infinite forms; the plotter tirelessly traces these curious algorithmic marks. It is here that Julien’s artistic work found expression, through the daily development of what has evolved into a highly personal visual language. And yet, before one can even discuss the vocabulary of this language, it should be noted that Julien has devoted considerable time to the writing of computer programs. A discipline that is inherent to the current view of algorithmic or generative art, and for which Julien has both practised with client work as well as more personal endeavours.

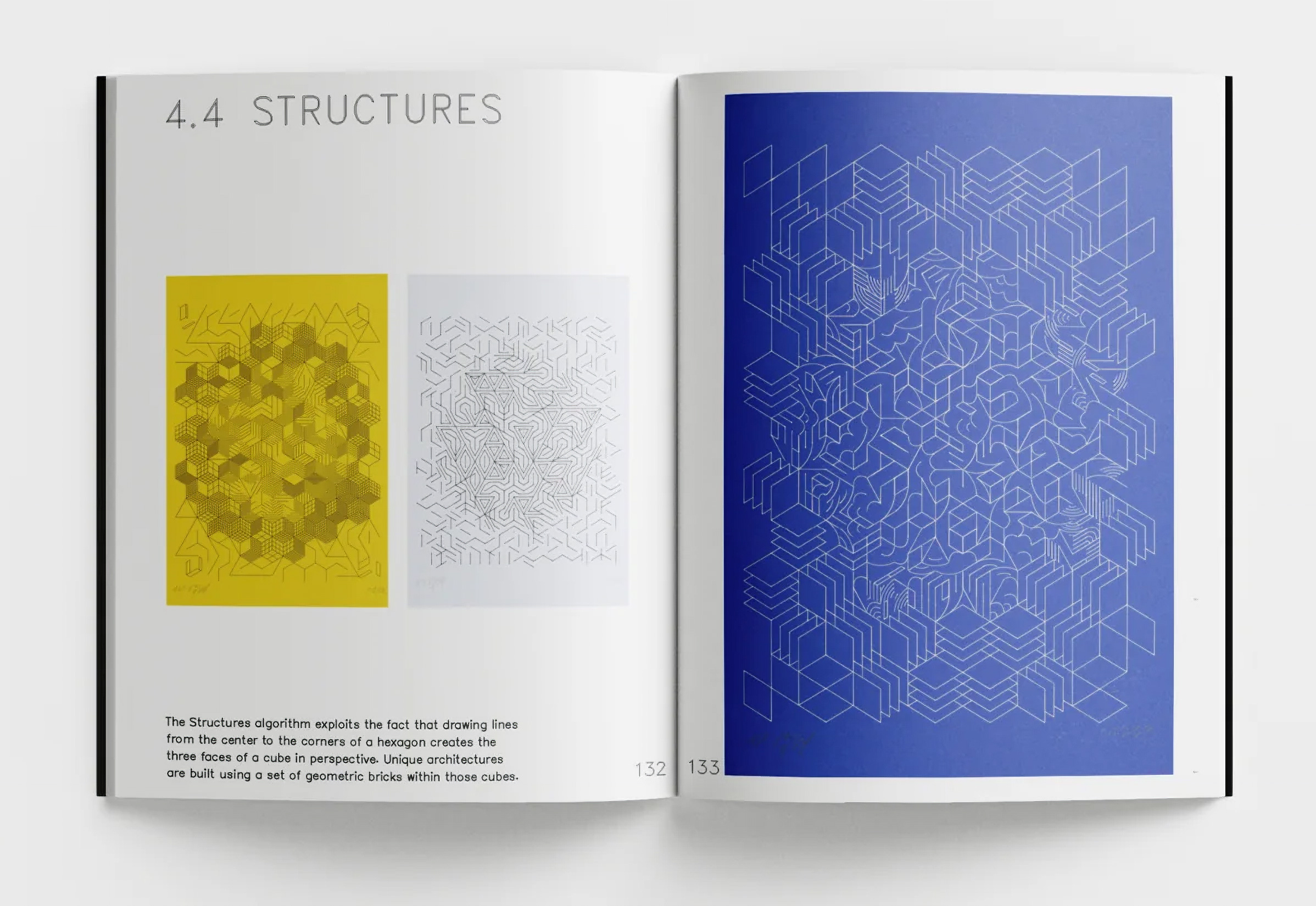

These programmes are his tools, refined over many years and which have come to define a specific set of algorithms. Indeed, these algorithms are his point of entry, a means to explore visual fields and find the limits of what the algorithm has to say. For the algorithm has deep roots in the language of mathematics which we have been visualising since the days of Euclid and reading (without us knowing) since the beginning of Islamic art. By honing in on these finer details, almost like a researcher observing a process, Julien has steadily built up a visual repertoire in which the vocabulary is constrained to pristine geometric lines, yet the visual expression seems boundless.

References can be pinpointed in Julien’s work to a long artistic tradition that began with the constructivists, became refined with the almost minimal work of the conceptualists, before finding a path with the computer artists of the 1960s. His work is constructed within this visual field of geometric abstraction. Julien is an avid reader of this history, sensitive to the rich yet relatively short cultural heritage of programmed art. I see the influence of Vera Molnar’s Interruptions (1968-69) or Hypertransformations (1975-76). Both series demonstrate underlying concepts that can be observed in his work, where simple graphic elements are laid out on a grid and randomness is used as a strategy to vary a number of parameters, such as position, size, orientation, or line length.

I could also draw a comparison to the plotter drawings that emerged from Manfred Mohr’s seminal exhibition in Paris in 1971, Une Esthétique Programmée. There is perhaps a connection here with the concept of the “étude”, a series of visual studies. When I look at what Mohr had produced for that exhibition, I see visual research – an artist attempting to express the possibilities of the algorithm and the drawing machine. Similarly, when I look at Julien’s extensive body of work, I also see the researcher at hand, seeking with each series the admiration of an algorithm and using a structured method.

Structure is a keyword in the work, and it is present throughout his series both in its methodology and its visuals. The rigour of rational application mirrors Julien’s great interest in mathematics, where beauty is revealed in the visualisation of the algorithm, and aesthetics find expression in the search for an objective harmony. There is structure in the concept of the underlying grid and the arrangement of a limited set of graphic signs. And while the repetition of these elements can reveal beguiling patterns, at times they are also displaced, fractured, with an element of randomness that introduces surprise and variation. The visual results are varied yet coherent, teetering on the verge between order and disorder.

Julien embarked on his artistic journey with the plotter in 2018, and since then there has been an increasing flurry of work from other artists using plotters. There has also been a growing interest in the field of generative art. While the two are historically linked and many speak of a revival, I sense something more profound has caught the eye of a small number of artists.

Working with a plotter brings a simple and clear sense of joy. This can be attributed to the physicality of the medium, where tangible objects hold a special meaning for us as humans because they elicit all the senses. While screen-based media monopolises the eyes, an object in our hands enhances our experiences by allowing us to touch, smell, even to hear. These sensations have a subtle yet profound consequence on how we perceive the image. Once it is taken off the screen and given another means of expression, it becomes a different thing entirely. We literally see it in another light.

The particularities of plotting extend our history of image making. Some may regard it as just another means of digital printing, but there is clearly more to the process than simply sending digits to a machine. For one thing, there is a strong link with the traditional art of working with tools and materials. The idea of marking a surface, whether it be with stone or pen, brings to mind the centuries-old concept of craft. When I observe artists with plotters, I see craftsmen at work, where it is fascinating to see how many are experimenting with machines and a variety of tools, papers, and techniques.

Considering skill to be a quality that one must practise daily in order for it to be acquired, Julien sits nicely amongst these contemporary craftsmen, diligently exploring a tool-set that evolves with each new path of iteration. From this emanates a body of artistic work, which is equally an expression of his commitment to an emerging and exciting field as it is of his structured method and careful thought.

First published in Pathways. Vetro Editions. 20.02.2024